It sounds like the plot of a fictional comedy. A group of gnarly Glaswegian factory workers decide to down tools – refusing to mend the engines of the fighter planes being used by a despotic junta thousands of miles away in Chile. One of them, an old ‘desert rat’ from WWII stands up to the bosses but is afraid to tell his wife that he’s risking his job through a sense of solidarity.

And then, after being left to rot for years, the engines suddenly disappear.

That’s just a fraction of the plot of Nae Pasaran. What makes it even more marvellous is that it isn’t a fiction at all, but a documentary, based on an act of trade union solidarity that has passed into legend.

Apparently, when the film premiered at the Glasgow Film Festival earlier this year, people were crying in their seats. UNISON’s Stephen Smellie, of the South Lanarkshire local government branch, says: “When I watched the film the first time I just felt so proud to be a trade unionist. It was one of the few occasions where I’ve felt ‘that’s me’ on the screen, this is what we do, we’re heroes.

“From a trade union point of view we do need to get this film out to everybody. It shows that trade unions are relevant, internationally, that solidarity works.”

On 11 September 1973, in Chile, the CIA-backed General Pinochet led the violent military coup against Salvador Allende’s left-wing government, which began with a frightening symbol of oppression – as fighter planes fired rockets into the presidential palace in Santiago.

In the days, months and years that followed, the dictatorship subjected the Chilean people to unspeakable terror: 3,000 people were killed, 30,000 were tortured and hundreds of thousands were sent into exile.

The warplanes that destroyed the palace were British Hawker Hunters, whose engines were made by Rolls Royce. And six months after the coup, a number of them arrived for maintenance in the Rolls Royce factory in East Kilbride, outside Glasgow.

As soon as he laid eyes on the engines, Bob Fulton, a Rolls Royce engine inspector, knew where he stood. “Dictatorship was a red rag to a bull to me,” he says in the film. He refused to touch them.

At first, this was an independent moral stand. But soon Bob’s union backed him. Then the AUEW (now part of Unite), its works committee voted unanimously to ‘black’ the engines, meaning that they were in dispute and not to be touched by anyone.

Later, the baton was picked up by the transport workers, who ensured the engines couldn’t be moved.

So while the Chilean air force champed at the bit for the return of its eight engines – its fighters grounded without them – they were left to rot in the factory. The film’s title means “they shall not pass”.

Years later, the story was one of many heard by Felipe Bastos Sierra, the son of an exiled Chilean journalist, living in Brussels. “I was eight when I first heard it,” he recalls now.

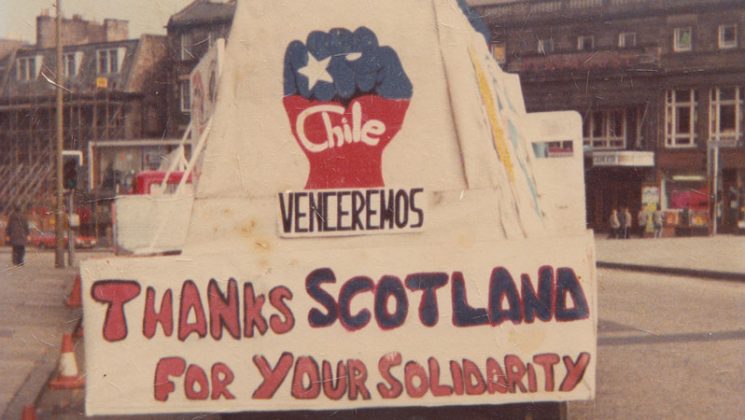

“It was carried by word of mouth, in Chile solidarity events in the ’80s where they would go through the list of support around the world. In Holland they refused to unload Chilean ships, for example, in France they were having these massive marches, and in Scotland there was this.

“The Scottish boycott of the Rolls Royce engines was one of the big myths of Chilean solidarity,” he adds. “It’s particularly significant for Chileans because the iconic image of the coup is of the Hawker Hunters flying over Santiago, firing rockets into the palace.

“And the idea that somebody had managed to dent that image by grounding those planes was incredibly uplifting – as equally uplifting as it was unbelievable.”

Left to right: Robert Somerville, Bob Fulton and Stuart Barrie

Felipe eventually moved to Scotland, became a filmmaker and, for one of his first films, returned to the Rolls Royce story. In 2013, he made a short documentary, just 14 minutes, which focussed on three East Kilbride workers and fellow stewards – Bob Fulton, John Keenan and Robert Somerville – and their efforts to prevent the engines returning to their evil owners.

“By RAF standards those engines were obsolete, they’d stopped using them in the late ’60s” says Felipe. “So this was second, third-hand equipment sold to very dodgy governments. A lot of dictatorships seemed to have them.

“And at that time, in the ’70s, East Kilbride was the only Rolls Royce factory with everything in place to fix them, which is what gave the workers their power. Once they decided to not work on them, nobody else really had the tools to do it.”

The director says that Bob Fulton, who’s now in his nineties, was key to the whole thing. “He was a world war veteran, in his early ’50s back then. And he was this incredibly colourful figure, which is part of the reason his boycott was successful. Everybody was, like, ‘Well if Bob’s against it….’”

Not only did the short film enjoy an enthusiastic response in Scotland, but it was warmly welcomed in Chile itself, by the then left-leaning government.

Not only did the short film enjoy an enthusiastic response in Scotland, but it was warmly welcomed in Chile itself, by the then left-leaning government.

Chilean soldiers line government workers on the streets

“When the short film premiered in Chile it dawned on people there that the story wasn’t a myth, it wasn’t a rumour, it was actually real,” says Felipe. “Within two days of premiering the film, I was in the Moneda Palace, the one that was bombed, having meetings with the ministry of foreign affairs, the minister of culture at the time, who saw the story as part of the Chilean heritage that had to be preserved.”

The government ministers also spoke about “giving recognition to the guys.” Bob, John and Robert duly received the Medal of Bernardo O’Higgins. O’Higgins was the liberator of Chile, and the medal the highest honour given to foreigners by the Chilean government.

The success of the short film also led to Felipe’s decision to make a feature-length documentary, which would flesh out the story. With this new film, Felipe talks again to the workers (now including eloquent fellow steward Stuart Barrie), tries to solve the mystery of what happened to the engines when they disappeared in the ’70s (which the workers knew nothing about) and adds the Chilean side of the story.

His interviewees in Chile include a former commander in chief of the Chilean Air Force (the chilling villain of the piece) and people in Allende’s government and sympathetic air force officers who were victims of the coup – tortured and imprisoned, but for whom the boycott of the engines had a tangible, emotionally uplifting impact that the Scottish workers knew nothing about.

The film was five years in the making and, not surprisingly, Felipe speaks of it as a “labour of love”. Combining his interviews with extraordinary archive footage and some engaging screen sleuthing, Nae Pasaran is at times disturbing, saddening and inspirational.

Felipe Bastos Sierra, far right, with the East Kilbride workers… and an engine

A UK/Chilean co-production, it was made with support from various bodies in the UK including BBC Scotland. But a third of the budget was raised through the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter, with a number of donations coming from UNISON and other trade union branches.

And UNISON is still helping this story reach as many people as possible.

Next week, on the 45th anniversary of the coup, Nae Pasaran will be having a series of one-off screenings in major cities. But this will be followed by a general release in up to 70 independent cinemas across the UK in November.

The union has been invited to be a funding partner in that release, with reps taking part in special screenings and using the events to engage with members.

To that end, UNISON’s Campaign Fund (formerly known as the general political fund) has agreed to back the film and is providing £15,000 to support the launch.

Campaign Fund chair Liz Cameron says: “The fund is all about the power of union campaigning. This is a great example that shows how one act of solidarity can change events across the world – that’s why we think its an important and powerful film.”

Regions interested in supporting a local release in November can contact David Arnold at d.arnold@unison.co.uk.

September screenings

10 September – Manchester – TUC Congress – £1 screening

11 September – London – Institute of Contemporary Arts

12 September – Glasgow Film Theatre

13 September – Dundee Contemporary Arts

14 September – Edinburgh – Filmhouse

15 September – Aberdeen – Belmont Filmhouse

17 September – Newcastle – Tyneside Cinema

18 September – Sheffield – Showroom