Two major judgments have been handed down concerning worker status in the gig economy. Both saw claims brought by drivers and both judgments went against the employers – Uber in the Supreme Court and Addison Lee in the Court of Appeal.

Worker status is important as it establishes a number of statutory rights, including rights to a minimum wage and working time rights such as paid annual leave.

The legal test for whether someone is a ‘worker’ is also very similar to the test for ‘employee’ in discrimination law under the Equality Act 2010.

Uber BV v Aslam [2021] UKSC 5

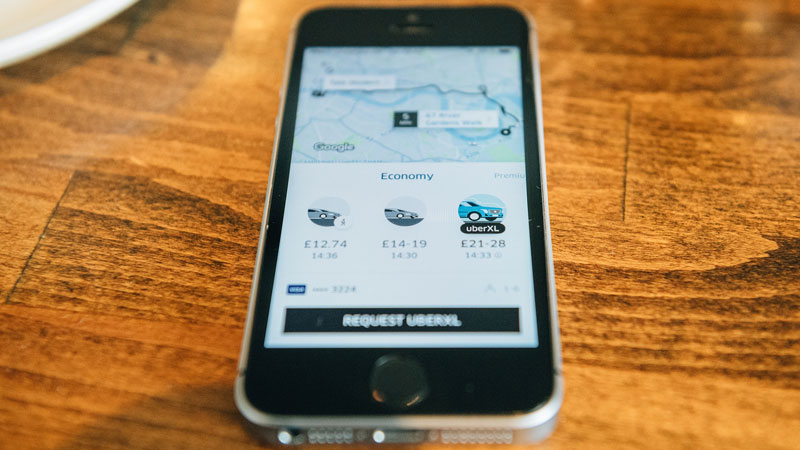

Uber controls an app that both car drivers and passengers can download, and through which drivers provide passengers with a transport service.

The main dispute was whether the drivers were workers of Uber or genuinely self-employed – particularly in circumstances where the contracts between Uber’s various companies and the drivers in effect characterised the drivers as self-employed.

Uber lost in the employment tribunal, Employment Appeal Tribunal and Court of Appeal. It appealed to the Supreme Court.

Resolution of the dispute essentially entailed consideration of two questions.

The reality behind a written agreement

First, when can employment tribunals look behind the terms of any written agreement between the parties?

It is now well established, following Autoclenz v Belcher [2011] UKSC 41, that tribunals can look behind the terms of written agreements between the parties.

Uber argued that this power was only exercisable where the reality of the relationship between the parties was inconsistent with the written agreements.

However, the Supreme Court found that the power was wider – tribunals can look at the reality of the arrangements between the parties and decide whether those arrangements establish worker status, even if those arrangements are technically consistent with the wording of the contracts.

This is because the employment rights in question are statutory rights, not contractual rights. The purpose of the legislation includes protection of workers in a weak position relative to their employers.

Given employers typically dictate the terms of written agreements, following Uber’s argument would allow employers to decide for themselves whether employment protections would apply to their workers.

Uber’s approach would also effectively facilitate a worker contracting out of their employment rights without going through the strict requirements in employment legislation for contracting out of rights – for example, an Acas settlement.

How much control?

Second, going behind the terms of the written agreements in this case, what was the relationship between the drivers and Uber?

The court decided that the employment tribunal was entitled to find that drivers were workers of employers.

The court placed particular emphasis on how much control Uber exercised over its drivers and the level of subordination. Particularly relevant factors included:

- Uber set the prices for passengers, its own service charges charged to drivers, and the terms under which refunds to passengers would be provided;

- Uber determined the terms of all the contracts, including the terms of the transport provision;

- Uber placed constraints on the driver’s control in accepting rides – including by keeping destinations unknown until a ride is accepted, and by applying sanctions for repeatedly rejecting rides;

- Uber vetted drivers’ vehicles, provided the essential technology, and used rating systems to control drivers, while drivers were limited in their contact with passengers.

Addison Lee Ltd v Lange [2021] EWCA 594

Shortly after the Uber judgment, the Court of Appeal delivered judgment in a very similar case concerning Addison Lee. The court refused Addison Lee permission to appeal against the finding that its own drivers were workers.

As relevant, Addison Lee’s model was similar to Uber’s – differences included that its drivers could not generally refuse journeys and had to provide an acceptable reason for doing so, and their vehicles carried Addison Lee insignia.

On appeal, Addison Lee focussed on its contract with drivers, which provided that there was no obligation on drivers to provide their services to Addison Lee at any time or for any minimum duration, and there was no obligation on Addison to provide work.

The Court of Appeal, following Uber and Autoclenz, found that the tribunal had been entitled to look behind this agreement and find that, when drivers were logged on to Addison Lee’s app, they were undertaking to accept the trips offered to them.

Both judgments have made clear that employment tribunals can focus on the reality of the relationship between parties – and not be constrained by the terms of any agreements.

The level of control that employers exercise will also be an important factor when determining worker status.

Accredited stewards and branch officers can contact UNISONdirect for urgent preliminary legal advice on employment matters. Call: 0800 0 857 857