Goodison Park, 21 February 1988. Everton were playing host to local rivals Liverpool in the fifth round of the FA Cup, when England striker John Barnes – who’d joined the club from Watford the previous summer – back-heeled a banana off the pitch.

Accompanied by chants of “Everton are white”, it wasn’t the first banana to be thrown at the only Black player gracing that game.

Everton chairman Philip Carter disowned the offending supporters, branding them “scum”. Arguably Barnes had the last laugh, finishing his first season at Anfield with a champion’s medal and the accolade of being voted Professional Footballers’ Association player of the year.

But John Barnes was not the first, or the last footballer in the UK to be on the receiving end of racist abuse.

One of the earliest recorded incidents in England came in the 1930s and involved Everton’s own Dixie Dean.

The Birkenhead-born centre-forward, who had a dark complexion, was subjected to racist comments as he walked off the pitch at half-time in a match in London. Dean reportedly punched the abuser, with a policeman then telling the latter he’d got what he deserved. No action was taken against the player.

As the number of Black players in the English game grew, so did the problem. Stars like Cyrille Regis, Laurie Cunningham and Brendon Batson – who formed a legendary trio at West Bromwich Albion in the 1980s – all faced abuse, including monkey chants and being pelted with bananas.

In 1993, five years after the incident at Goodison Park, Kick It Out was launched to lead and co-ordinate equality and diversity training for professional footballers at all levels.

Twenty-five years on, the organisation continues to provide support by mentoring young people who aspire to careers in football, as well as working closely with football authorities, clubs, players and communities to tackle all forms of discrimination.

It also provides a facility for football supporters to report incidents of abuse, both via its website and through a mobile phone app.

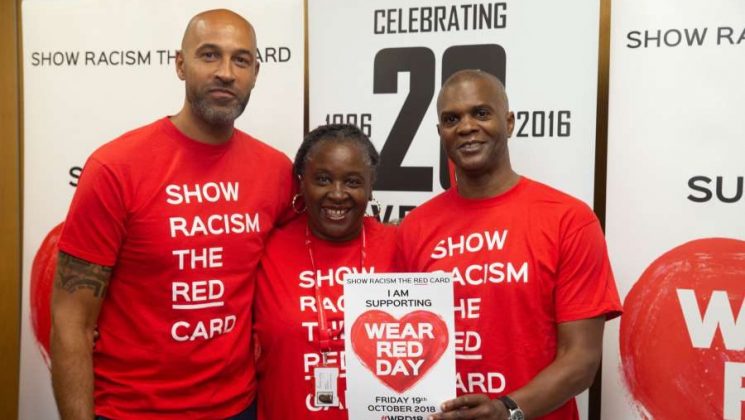

Three years after Kick It Out came Show Racism the Red Card. Established in 1996, the charity utilises the high-profile status of football and football players to publicise its anti-racism message across society as a whole.

It too continues to provide educational workshops, training sessions, multimedia packages and a whole host of other resources – delivering training to more than 50,000 people every year, all with the purpose of tackling racism.

Paul Davis spent 15 years at Arsenal, amassing 446 appearances and 30 goals as a midfielder, winning League and FA Cup medals, along with a Cup Winners’ Cup medal, and captaining the England under 21 side. He is now a senior coach/coach educator for the Football Association (FA) and an ambassador for both Kick It Out and Show Racism the Red Card.

Jason Lee, a much-travelled forward whose playing career included Charlton, Notts County and Falkirk, plus a spell as manager at Boston United, is now an equalities education executive for players’ union the Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA).

The two men spoke to U before the launch of Show Racism the Red Card’s Annual Wear Red Day, in October, the national day of action that raises money towards the delivery of anti-racism education for young people and adults throughout England, Scotland & Wales.

Jason Lee

“I’ve been involved in football professionally since ’77,” says Paul. “As a player, back then, it was really, really tough, up and down the country. It was a daunting prospect.”

Though Jason is of a different generation to the likes of Paul and John Barnes – his playing career lasted from 1989 to 2010 – he says that he still had to deal with “racial elements in the game.”

Both he and Paul feel that the situation in today’s soccer environment is much improved. But the problem is far from over.

According to a 2017-2018 mid-season study, Kick It Out received 308 reports of discriminatory abuse by the end of 2017 – an increase of 59% on the same period of the previous season (177 incidents).

Covering the professional game, grassroots football and social media, the report breaks down the abuse as:

- 54% racist;

- 22% homophobic, biphobic and/or transphobic;

- 9% anti-Semitic;

- 7% disablist;

- 6% sexist;

- 2% Islamophobic.

Little wonder then, that Jason is keen to urge vigilance. While he believes the days of banana throwing are over, he observes that “it only takes one or two people” to instigate abuse.

Importantly, there are now mechanisms in place to deal with racism. And education is key. Jason works in equalities, and Paul has been involved in similar workshops and initiatives, educating both players and fans about how to behave.

When they were playing themselves, there was no education around the subject. “To survive and stay in the game, we just had to deal with it,” says Jason. “That’s what we were told. Whereas now, players realise they can take a stance.”

Paul recalls that, “I wasn’t encouraged by my club to take on situations, where they probably should have been taken on. Back then, they’d say we just had to ‘turn the other cheek’.”

Continues Jason: “Now, players are not told that. Their wellbeing, their mental health is a big thing.”

Given that, what did they think about the way that Manchester City and England midfielder Raheem Sterling was treated during England’s World Cup experience this summer, particularly by the Sun, which tried to get the player thrown out of the squad on the grounds of a tattoo of a gun on his calf. During the tournament itself, Sterling’s ratings from the public were lower than all but two of the squad who took to the field – despite his terrorising of opposition defences.

“It was over the top – as per usual,” says Jason, citing former Arsenal icon Ian Wright’s comments that the criticisms were motivated by racism.

“I thought Raheem handled that situation very, very well. He came out, spoke about it. He explained the reason why he’s got a tattoo and what it represented [he lost his father to gun crime] and, I think, once people saw that, they thought: ‘Okay, maybe I can sympathise’.”

Paul nods in agreement, describing Sterling’s handling of the situation as “exemplary”.

He adds that the vastly increased number of Black players at all levels of the English national side illustrate the positive changes that have taken place since his own playing days.

But he also points out that, while playing opportunities have increased, there’s still an obvious lack of Black managers and coaches.

“That, for me, will be the next area that we need to look at in this country. We’ve come a long way, but there’s still a hell of a long way to go.”

UNISON has been working with and supporting Show Racism the Red Card since it was founded.