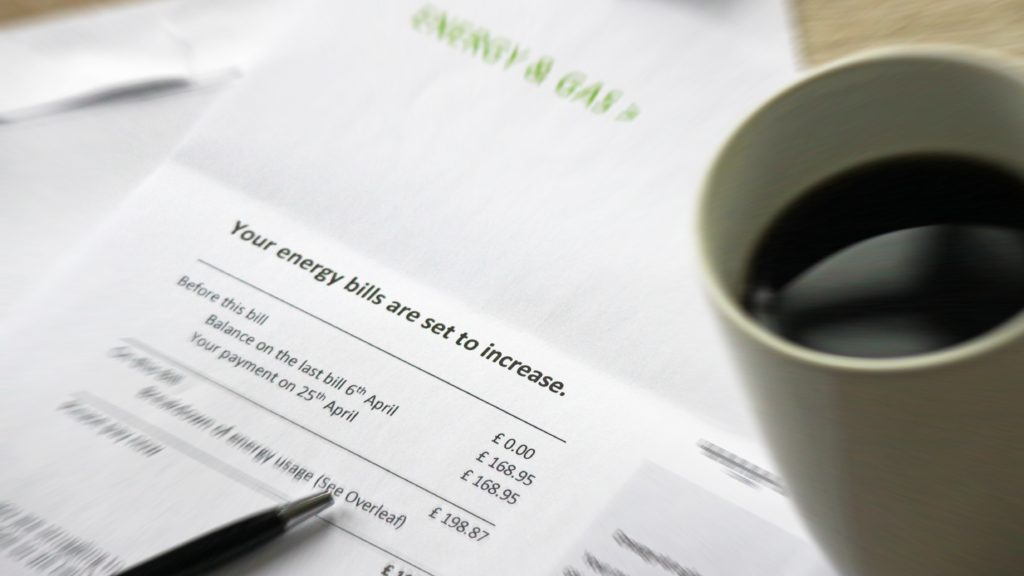

You’re already feeling it – waiting nervously in the check-out queue at the supermarket, or when you open up a gas or electricity bill, or when you’re filling your car at the petrol station. And when you’re looking at your kids, thinking of birthdays, or the new school uniform they really need.

But why are we in this mess? Where on earth did this crisis come from? UNISON has turned to two of its experts, to explain the root causes, the nitty gritty of the cost of living crisis.

If the cap fits

One of the most serious areas of concern for many people will be the extreme increase in the cost of energy. Matt Lay, UNISON’s national energy officer, talks about the energy price cap – what is it, why has it gone up and what should happen in the future.

The price cap was introduced by the government as a measure to protect consumers who didn’t switch or shop around and, therefore, remained on default tariffs. It was felt that these customers weren’t benefitting from the energy market which existed.

The cap is set by the energy regulator Ofgem and is reviewed twice a year, although this may change to four times a year under new proposals. It takes account of the movements in the wholesale price of energy (gas and electric) which has taken an extreme upturn over the last year.

Although it is quoted as an annual figure, based on typical household consumption, the cap itself is a maximum charge per unit an energy supplier can levy, so how much you pay would depend on how much you use.

What will the energy cap going up mean for me?

In a typical household, the energy price cap has risen from £1,138 pre-October 2021 to £1,971 in 22 April. Some have predicted that it could increase again in October to close to £3,000, depending on movements in wholesale costs.

Remember, your total energy bill is linked to how much energy you consume. If you live in a poorly insulated home or do not have a modern boiler you are likely to consume much more energy to achieve the same level of comfort than those who live in well-insulated homes.

It is generally accepted that lower income households live in the most poorly insulated homes, so they end up spending a much higher proportion of their income on energy.

What could have been done to stop it?

UNISON has long argued for a national programme of energy efficiency measures to ensure every UK home could reach an EPC (energy performance certification) level of C with a longer term aim of getting to a level B.

This programme would have been universal, going door to door to ensure these standards were met. Those able to pay would have benefitted from interest free loans set against the property – not the person – and those low-income households would have received the works free of charge.

This would have saved consumers an average of £600 per year and helped them weather these storms much better. Furthermore, it would have made a huge dent in our carbon emissions and created over 100,000 jobs.

UNISON also argues for public ownership of the energy retail supply business. In part, approximately two million customers were already nationalised by default when Bulb went into special administration. With energy prices pretty much already being set by the regulator and the mistakes of the energy market laid bare for all to see, now is the time to act.

Such a move would cost relatively little to achieve and would ensure the government could act as the French government has done and limit price increases with immediate effect, bulk purchasing energy and protecting householders through direct taxation not regressive levies on bills.

This would also enable the energy efficiency programme to get going without delay or complication, utilising the skills of UNISON members in the industry and giving more secure employment.

What’s in the pipeline?

The Westminster government has simply not done enough to support consumers. This needs to change – fast – to avert a catastrophe this winter when the price cap is set to rise again.

With bills going up, suppliers are worried that the system could be close to collapsing and those without the means to pay will go cold. The current government actions are like putting a sticking plaster on a gaping wound.

In the meantime, if any energy customer is experiencing difficulties in paying energy bills they should get in touch with their supplier without delay and seek help and support.

Inflation

Simply put, inflation is the increase in prices over time. But what does that actually mean for you? We spoke to Kevin Russell, national officer with UNISON’s bargaining support unit, to find out.

How is inflation measured?

The most widely reported measure of inflation is CPI – the consumer price index which, in effect, calculates the change in how much it costs to live in this country. CPI takes account of the price of food, drink, travel, clothing, education, culture, housing and bills, among many other things.

However, UNISON believes CPI fails to adequately measure housing costs and is less representative of the experience of the working population than another measure called RPI – the retail price index – which incorporates a lot of the same elements but averages them differently.

In March 2022, the CPI stood at 7% over the previous 12 months. This meant that prices went up by 7% compared to the same point last year. In March, RPI stood at 9%. This level of inflation hasn’t been seen in over three decades.

What does that actually mean for me?

Between the start of 2010 and the end of 2021, the cost of living, as calculated by the RPI, rose by a total of 45.8%. Had your pay packet increased at the same rate as RPI, you probably wouldn’t have noticed the change. But for the vast majority of the population, that hasn’t been the case.

For the average public sector worker, the real value of their pay packet has been cut by 14%, leaving their 2021 wage over £5,600 down per year on the value of their earnings in 2009. The accumulated loss from their wage failing to keep pace with inflation, since then, is £44,000.