Are you among those who are frustrated by what now seems like an eternity of bad behaviour in the corridors of power at Westminster? Depressed by the apparently endless gaslighting of a government less interested in governing than in creating division.

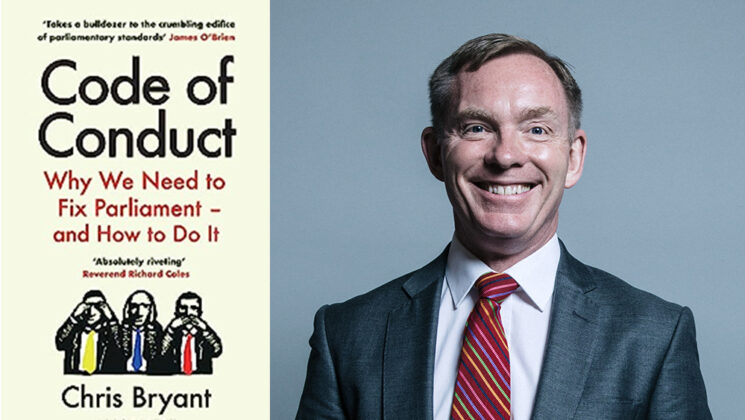

You’re not alone. And Labour MP Chris Bryant has laid out the problems – and some solutions – in his new book, Code of Conduct: Why we need to fix Parliament – and how to do it.

A bit of context never goes amiss. Bryant points out that, in the long history of politics in SW1, there have been a wide variety of parliaments – many with defining nicknames.

Mad, Bad and Merciless

There’s been the “Mad Parliament, the Model Parliament, the Unlearned Parliament … the Long, the Short and the Rump Parliaments.” The Good Parliament of 1375 tackled fraud and corruption in the court of Edward III, but was followed the very next year by the Bad Parliament, which undid that work.

Then there was the Merciless Parliament of 1388, which Oxford historian Professor Jonathan Healey says might have been formed by “forcing a nest of wasps to mate with Katie Hopkins, and cramming their multiple spawns together into a poorly ventilated Wetherspoons toilet”.

So how would we characterise our current iteration, asks Bryant? A ‘Parliament of Shenanigans’ perhaps, or the ‘Pinocchio Parliament’?

The MP for Rhondda has been chair of the standards and privileges committee since 2020. And he notes that, since the general election of 2019 and at the time of writing, 22 MPs have either been suspended by the House, resigned their seats or left the chamber before being suspended for a day or more – “the worst record of any parliament in our history, by a long chalk”.

A large part of the problem stems from the lack of a written constitution. A ‘gentleman’s agreement’ doesn’t count for much if there are no gentlemen present.

Some issues and solutions

Bryant covers a range of issues, including lobbying, second jobs for MPs, the whips system, private members’ bills and the way control over the order of business has been taken over by government.

His approaches to some of these might surprise. He is far more nuanced on the whips system than might be expected, believing that, if an MP is ideologically at one with their party, there shouldn’t be a problem with whips, but also that parties need to allow for a little rebellion around the edges.

On second jobs, he would not bar all – and not only explains why, but offers a list of what sort of second jobs should be allowed and how they can fit in with a members’ responsibilities to their constituents. It is an interesting point that becoming a minister is, in effect, a second job – and one where it is likely that constituents will see far less of their elected representative than when they were a backbencher.

Bryant is never partisan, citing good and bad examples of MPs’ behaviour from across the House, and stressing the importance of collegiate working. This is particularly clear in committees, where so much of Parliament’s work is done – something that was more apparent than usual this year in the report of the privileges committee, where Conservative MPs hold a majority of seats, into the behaviour of Boris Johnson.

Filibustering

Bryant is also at pains to acknowledge his own failings. Early on, he quotes Tory MP Christopher Chope as saying, “he [Bryant] thinks very highly of himself”, before adding himself, “and he probably has a point. I like the sound of my own voice”. Later, when discussing insincerity from MPs who have been ordered to apologise to the House, he includes, as a footnote, one of his own apologies.

He’s perfectly clear, though, in his contempt for the likes of Jacob Rees-Mogg and Chope, the latter a perennially hypocritical filibuster who loves nothing better than to stymie other MPs’ private members bills, even to the extent of putting forwards dozens of his own to tie up the system.

Code of Conduct is a short read at just over 200 pages, but packed with information and detail. It’s also unputdownable – helped by Bryant being both a self-confessed Parliamentary geek and a good writer.

The ideas presented are sensible and could make a major difference to restoring faith in how our political system works.

It might seem minor, but Bryant would like to see an end to the government’s exclusive control of the Commons order paper and timetable, “handing it to a cross-part Business Committee, elected by the whole House, which would … guarantee time for government and private members’ legislation and ensure enough time is allocated for all important or controversial legislation.”

The book is both damning and, in terms of what could be achieved, optimistic. Not for nothing, Bryant would like to see a ‘Fixed Parliament’ – in this instance, nothing to do with parliamentary cycles and the mechanism for calling elections, but “mended”; though he suspects we’ll have to wait for a new one before there’s any chance of that happening.

Whoever does form the next government, they should take more than a few lessons from this book, for the sake of Parliament itself and us all.

Code of Conduct: Why we need to fix Parliament – and how to do it by Chris Bryant and published by Bloomsbury, is available now in hardback.