UNISON’s disabled members conference takes place in Edinburgh this week (28-30 October). The first motion to be debated, prioritised by the delegates themselves, is about the experience of workers who are neurodiverse, something employers and society are only now starting to understand.

The motion deals specifically with the huge lack of understanding about neurodiversity as it relates to women, with neurodiverse women still failing to get the support they need in the workplace because of outdated and sexist stereotypes.

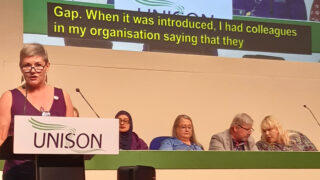

Lisa Dempster (pictured above) is one delegate in Edinburgh who knows all about neurodiversity – as someone who is both autistic and ADHD, has a neurodiverse child, and has spent several years working with disabled children.

And, she says, “I am so passionate about disability awareness. I’m open about my own disability because I want people to ask me questions and understand my condition.”

Diagnosis

Lisa has worked for Knowsley Metropolitan Borough Council, in Merseyside, for 34 years, the last five as a support worker with a children with disabilities social work team. She’s also doing an apprenticeship in social work at university. With UNISON, she is the North West disabled members chair and sits, for her region, on the national disabled members committee.

It’s an impressive list of accomplishments, alongside that of raising three children. And it’s all the more remarkable given the challenges she’s had to deal with, for most of her life.

Lisa was diagnosed with autism five years ago, at the age of 47. Six months ago she was diagnosed, additionally, with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Ironically, she self-referred for an autism assessment as a result of researching the condition when her child Phoebe (who now identifies as non-binary) was experiencing problems at school.

“I started doing a little bit of research into what autism looked like for girls,” she recalls. “And remember reading a case study and thinking, I could have written that. That’s my life on paper. And then I thought, could I be autistic?

“Throughout my adult life, there was a lot of poor mental health. I was diagnosed with depression, I was diagnosed with anxiety, I was diagnosed with two eating disorders. There was a question mark around borderline personality disorder. I’d seen psychologists and counsellors and psychiatrists, and everyone was like, ‘it’s this … it’s this’. But I always felt as if there was something more. I didn’t know what ‘more’ was. What they were saying to me just didn’t seem to fit.

“And the more I looked into it, the more it made sense. Autism made sense with situations I’ve gone through in my life, how I think, how I deal with things, how I need to process things.”

What is neurodiversity

Neurodiversity refers to the different ways a person’s brain processes information. It is an umbrella term used to describe a number of variations, which include:

- Autism, or autism spectrum conditions

- ADHD, or attention deficit disorder (ADD)

- Dyslexia

- Dyscalculia (difficulty performing mathematical calculations)

- Dyspraxia (difficulty performing coordinated movements).

It is estimated that around 1 in 7 people in the UK have some kind of neurodifference.

The male-based toolkit

However, Lisa found that getting the diagnosis wasn’t straightforward. She experienced what she calls the “male-based toolkit”, when her first assessor, a man, told her that she met the criteria for ADHD but not autism.

“This is very gendered,” she says. “Autism was always seen as a male condition, and they’re still diagnosing under the male criteria. I know from my research that women present very differently than men. Autistic girls are more able to copy other girls, learn their social cues, how to interact with other people. Apparently boys’ brains don’t do that. So this ‘masking’ makes it’s more difficult to identify autistic girls.”

Moving forward

Lisa knew enough, and was confident enough, to seek a second assessment, which did diagnose her as autistic. And, rather than a terrible blow, it was a positive step forward for her.

“Since getting that diagnosis, my mental health is probably the best it’s ever been,” she says. “Because I’ve got answers to why I was like that. I’m not broken. I’m not ‘wrong’. I’m not stupid.”

She wasn’t surprised when she was later diagnosed, also, with ADHD. “You will often find that neurodiverse people will have more than one condition. And every one of those conditions has its own difficulties. How I try and explain it, for me, is that I’ve got this autistic side of my brain that likes routine, that likes order, that likes things done in a certain way, that can be quite rigid, that doesn’t like change, it can create black and white thinking. And then I’ve got this ADHD side of my brain that is just absolute chaos – it’s here and it’s there, it’s literally like you’ve got a tangled ball of wool.

“All day, every day, that’s my brain. And I’m trying to do a job and I’m trying to go to university and I’m raising a family and I’m running a home. And we’re expected to fit into this world that’s not designed for neurodiverse people. Even with reasonable adjustments in place, we are still expected to be less autistic or less ADHD in work, because there is an expectation of how people have to behave.”

Personal strategies and reasonable adjustments

That begs the question, how can neurodiverse people survive – and thrive – in a society that is built for neurotypical people?

“Well, you have your own strategies.” She laughs: “This is the extreme example. I might sit there and think, ‘Oh, I wonder what would happen if I strip naked and run through the office?’ Now, I’m not going to act on those thoughts, because I know if I did that I’m gonna get sacked.

“But it might be, I’ve got this meeting for an hour, and I’m feeling quite fidgety because of my ADHD. So I’ll have a fidget toy under the desk. So I’m fidgeting, but I’m able to concentrate.”

As for reasonable adjustments, Lisa’s own experience is positive. Each time she approached her managers, after both the autism diagnosis, then the ADHD one, the response was, ‘Okay, how can we support you?’

As she’s suggested, Lisa already had her own strategies, and therefore wasn’t sure what to ask for. But there have been two very useful adjustments. The lack of a guaranteed parking space and the requirement to hot-desk were both causing her massive anxiety, so that by the time she arrived at work both things were all she could think about. The solutions: since there was no staff parking, her senior manager arranged a permit in a visitor’s area; and she was given her own desk.

“This is how simple it can be – I’ve got a parking space, and I know where my desk is going to be. And, I can tell tell you, it makes a huge difference. When we talk about reasonable adjustments, it isn’t always this massive thing that we need. I’m not having special [treatment] over anyone else, it just puts me on an even playing field when I come into work in the morning. There probably are other reasonable adjustments that I could use, but at the moment that’s all I need. And I’m doing okay.”

She mentions one more, though. The same manager, knowing that Lisa struggled with meeting new people, would bring anyone new to the office to come and meet her. “It’s little things like that, which make me feel like you’re listening to me, and understanding me and supporting me.”

‘We’re not all math geniuses’

A similar sort of adjustment – a better word might be ‘courtesy’ – applies to her child, who’s now 15, at school: whenever there’s a new or returning teacher, Lisa thinks the obvious thing to do is introduce them to Phoebe before going into the first lesson, thus easing their anxiety about this new person.

Phoebe’s autism assessment took a lot longer than Lisa’s, an appalling four years (another issue in the country’s mental health landscape, at present, is the time it takes to be assessed, not least for children). They are also diagnosed with Tourette Syndrome and, Lisa thinks, may have ADHD. When telling me this, Lisa brings up an interesting and important new perspective on the subject.

“People often look at you and think, ‘Why are you getting your child all these labels?’ It’s not that we want our children to have labels, but my daughter was already getting labels from school – as lazy, disruptive, naughty. And I had all those labels throughout my school life, because obviously I was undiagnosed in my childhood.

“I was made to feel at school that I was never going to amount to anything – and I’m in university now. I want the correct labels, so that if my child is struggling, the teachers understand why and deal with it. And if my child decides to go to college, I want to know they’ve got the correct diagnosis so they can say, ‘Right, this is what I need you to give me, to support my learning’.”

While we talk, Lisa frequently invites me to “shut me up”. But there’s absolutely no need. She is fascinating, funny, passionate and completely on top of her subject. I’m not sure whether this is because she’s been told, too often, that she talks too much, or whether it’s one of her strategies, to make her feel more comfortable about her mode of conversation.

She agrees that the media, including films (Rain Man springs to mind), have narrowed people’s view of what it means to be autistic – the genius with no social skills.

“We’re not all math geniuses,” she asserts. “And I can be the most sociable person in the world – on my terms. When you’ve met one autistic person, you’ve met one autistic person. We’re all different. We’ve all got different strengths, we’ve all got different weaknesses.”

Lisa has a simple, but passionate message for the world at large. “Stop trying to make me be less autistic. Just try and accept my autism. We’re still fully functioning members of society. If you can give us just a little bit, we will give you so much more.”

We have used Lisa’s language throughout this article. UNISON supports the social model of disability, but we also appreciate that individuals, including neurodiverse people, need to be able to describe their own experiences.

Thankyou for speaking up! I support my AuDHD adult daughter, and all the issues you speak about applied to her and her diagnosis journey. A lot more needs to be done to raise awareness, understanding and acceptance – in all areas of life.

Thank you, I am dyslexic and suffered depression and I always felt I was not good enough. Being black was a added obstacle, I feel like I have struggled a long time with no support.

Thanks Lisa for sharing hoe your correct diagnosis has helped you in your life.

I’ve had similiar previous diagnosis and was relieved when I got an adhd diagnosis earlier this year, speaking with a psychiatrist who had adhd too really helped me feel like I could cope and even thrive going forward in my life. I am not medicated for adhd as I’m not suitable for it, and I reached out to a therapist instead, which in turn has freed me up to reconnect with my crazier funnier less tense self. At times, there are the shit days still, but I’ve not felt this content and excited about my life, my future for decades!

As for adjustments, I get the parking frenzy! I also need information printed out, in order to retain the information I actually need to rewrite out what I’ve read. Its how I studied at school, and its still the only way to put stuff into memory.

Making sense of my fractured brain, my contradicting thoughts, or knowing I don’t have to make sense of it or be perfect for anyone (being good enough is all thats needed)

I do tend to need to work extra, do more than is required, it makes me happy. I guess it can be annoying if there are time constraints!

Plus I am sharing personal information here, I used to hold everything because I thought I was so messed up, I wasn’t and I’m not, I’m me, don’t like it, don’t have to!

All the best for you Lisa and your family.

Thank you for this article Lisa!

My journey is a similar one, diagnosed at 45, single parent of three (two that have labels re: neurodiversity), whilst holding a professional career.

My experience is not a good one and still an ongoing struggle in the work place after nearly 3 years of waiting for reasonable adjustments!

They don’t just affect our work but our quality of life.

I too have a passion for raising awareness, I wish I could apply my experience and knowledge where it is listened to, such as what you have done here.

Sincere thanks. If it is possible to get a copy of this article to share, I would appreciate it, as it is worded perfectly.

Equally I am all for getting involved in any way possible to spread awareness and create a better world for us to share

I received a diagnosis for dyslexia at 31. Always been open about it but never felt I could really ask for adjustments. I can do the job even with or despite my dyslexia. Asking for help would make them think I was less capable. I was unaware of the unison disabitiy conference this is something I would have been interested in attending.

Another one here! I’m 45 and on a waiting list for diagnosis but I’m certain. Also started asking questions after diagnosis of my son. I may mask better but he’s so like me. Thanks for sharing and raising awareness. I wondered whether to bother with a formal diagnosis, but as my husband said it’s “future proofing” which is incidentally the reason I’m in unison. Everything may be good at work right now, but you never know when that will change.

Dear Lisa

thanks for your amazing article. I am a Steward for unison. My daughter has autism she was diagnosed at 24, she had a horrendous time at School bullied and even though she was high functioning scrapped through her exams. She is a single mum of a child who has also got autism and like you we want to ensure the child has a better experience in education. One of the things we struggle with is the lack of information and support for autistic parents with autistic children. There is little research or guidance. Can you recommend any books or any support groups. Keep growing and championing this cause . I am dyslexic and my husband has ADHD and dyslexia. We all work and our employers have been amazing at making our work life happy in our neurodiverce world. Best wishes to you and your family

As wonderful as this is, it is not my reality. I have been bullied by colleagues and management in the NHS, and the Unison rep did not help me in any way. I fact she contributed to the abuse by neglecting to support my accommodations requests.

I pray more is done to expel the ignorance and cruelty in large organisations, so the wonderful Neuro diverse employess can excel in their chosen field within a safe environment. We need safety to unmask.

Thank you for this . I was diagnosed autistic at 66 years old . I’m still working but find my colleagues are quite “off” with me . Lack of understanding more than malice .

I have an iq of 159 and aviation and space are my special subjects . So mad genius fits well .

A really interesting story. Bravo for putting yourself out there.

Where did you go to to get self-diagnosed? We are in the same situation and have little money for counsellors and struggling to get a GP appointment.

I loved reading this, especially the part about labelling a person. The fact is that people get labelled and categorised, so lets make sure they are the right labels and that we are treating each other in ways that encourage everyone to be their best self.

Dear Lisa

your story could be my story; thank you for speaking up.

it is so good to hear other neurodiverse people’s life stories and experiences.

kind regards and best wishers

Anita

Thank you for sharing Lisa particularly the part about labels, and this is why a lot of people wont enquiry about help and support it seems in my experience, to put people off. As you say people can be labelled in the most appalling way which is no help at all. With the right help and support to be understood and listened to, instead of feeling pressure and anxiety.

I do hope there is a lot more help and awareness and much quicker process for children and adults. Thanks Lisa

Great article, thanks, I have a child with a diagnosis and really important to talk about and break down barriers

Thank you for sharing Lisa, it seems to be such a battle to get others to understand neurodivergent staff in the workplace as everything seems so generic however sharing stories and standing up for Neurodiversity is the beginning!

Thank you for sharing your experience with everyone as it helps to educate people and hopefully raise awareness about the difficulties and challenges that people face in all aspects of their lives. It is great to hear Lisa’s story from her own viewpoint and incredibly brave and inspirational.

I have also struggled through my life in many different aspects for as long as I can remember. I have been misdiagnosed with many different mental health problems in the past; from depression all the way through to bipolar disorder amongst many others. I am still on the waiting list to be assessed for ADHD and I have more hope that I can be better understood and accepted in my workplace in the future instead of trying to hide my uniqueness and apologising about my crazy ways!

I really hope that thie higher management will be able to implement better educational practices and outcomes for the future so that more people are aware and accepting of the benefits and difficulties of thinking outside of the box.

Good luck for your very bright future and all of the wonderful people who will benefit from your great work.

Thank you for sharing your story. I too am Autistic and diagnosed in my mid 30’s. For some miraculous reason I have managed to work my adult life in various healthcare settings but it has always been an up hill struggle.

This is my first job that I have requested reasonable adjustments and after several meetings. The adjustments were granted. I still have good days and bad days this week happens to be a rough patch but your story has come at on opportune time.

Thank you again.

My son has recently been diagnosed at age 28 with ADHD. We are all learning as a family how to support him and he is gaining confidence in how to ask for help in the best way. I found your article vulnerable and interesting and send my best wishes to you.

Lisa

such a great article, I have just realised why i choose not to drive, there are too many variables I cant control, parking, fuel, traffic jams… it all makes sense

thanks

MK

I was diagnosed as autistic when i was 47 in 2018, and have had a less positive experience tbh. My employers made no attempt to cater for my condition and i have had to fight to get reasonable adjustments made. However it is good to see an autistic woman in a position of authority in UNISON.

I rarely read articles send to my work inbox as life is so hectic and work so busy. But this one caught my eye and I am so glad I read Lisa’s story. Lisa your story is so authentic, it opened my eyes so much more to the experiences of neurodiverse people and the uniqueness of every person. In my work I come across children who are neurodiverse and parents who struggle to get appropriate diagnosis and support and I will share your article with them. your message is powerful! Thank you for speaking up!

Thank you Lisa for this very insightful article and why we may have to give these issues labels as they will not otherwise be addressed properly.

If we don’t recognise neurodiversity we will not be able to address it and obtain appropriate support.

Your story was inspiring, Lisa.

I have AS myself and in fact with the help of Unison made legal history with it: I successfully sued my employers after getting turned down for a promotion because of my AS – http://www.ealingtimes.co.uk/news/690195.councils-appalling-treatment-of-autistic-worker-in-landmark-case/

My experiences at school largely mirror yours, although I suspect mine were worse due to my gender. But it wasn’t until 1999, at the age of 30, that I was diagnosed. Although on the one hand it’s completely killed any ambition I may or may not have had (prior to the diagnosis I was always able to point out why it was their fault not mine when I lost a job or resigned under a cloud, but afterwards it was clear that the issue was with me and I couldn’t escape it by running away) it has OTOH given me answers to the phrase I’ve heard so many times “there’s something about Mark that I can’t put my finger on”

I am now far more accepting of it and comfortable with who I am.

Stay well, Lisa

Thankyou. I was the clumsy, ‘always in the wars”, doesn’t concentrate, could do better” child… and thorough my working career (now a Local Authority Social Work Manager) I have made light of what I considered my ‘eccentricities’ and no doubt benefit from working in a service supporting teenagers where difference and diversity is valued: But at the age of nearly 50 I have had Dyspraxia confirmed and awaiting assessment for ADHD. I was in two minds about pursuing it as it feels like a bit of a label: and my mind is capable of amazing things because of it’s neurodiversity, there really are positives. But if we could all be more accepting and valuing of difference it would be brilliant. It makes me sad how much I had internalised criticism at school and work all these years!

Thank you for this, Lisa. I suspect I am autistic after one of my children was diagnosed a few years ago – I had always thought there was something wrong with me, that I couldn’t human like other people, but never thought there might be something with a name until my child’s diagnosis. Now I’m saving up for a private assessment because even though it’s probably years too late to make any difference, I would like to know for sure.

Being a late diagnosed autistic (+ADHD), I have had to reassess a lot. I have come to the realisation that a lot of work places have toxic/harmful environments for the neurodivergent person. With managers often using gaslighting and ableism as strategies.

Unison still have a lot of catching up to be effective supporting us.

Thank you for sharing your story Lisa and speaking so openly. There needs to be more open, affirming and accepting discussions around neurodiversity. My 6 year old daughter is on the waiting list for an autism assessment. I recently requested a referral from my GP for myself, as my research to learn more to enable me to fully support my daughter has been a massive light bulb moment for me. Unfortunately, I was told there was no point in submitting the referral because Psychology Services in Fife are overwhelmed and they currently have a very strict referral criteria for adults. I was told to implement the learning when my daughter receives her assessment, but who knows how many years that may be away.

A fascinating story thank you. I wish I could have read this before my career involved supervising staff.

Thank you for sharing your story.

Maybe we can have some more stories like Lisa’s.

Thanks Lisa and all those who have commented. I support my daughter who finally got an ADHD diagnosis at 18 years old, having struggled through school. We are still waiting for an autism diagnosis for her, but I am sure it is coming. This is all educational but, in particular, what Lisa says about the two sides of her brain helps me further in understanding my daughter’s world.

Thanks for sharing your experience it was so insightful and makes me think that everyone needs to know more about neurodiverity. You were lucky to have an employer who said: ‘Okay, how can we support you?’ and were offered resonable adjustments. Hot desking in a previous role caused me anxiety too but my line manager said that only the person with the physical disability could have a fixed desk, luckily this was witnessed by my Unison Rep and adjustments were put in place.

I was diagnosed with BPD at 30 then diagnosed with Autism at 39 then with ADHD at 42 and my entire life ive never felt like ive fitted in. With these diagnosis i now know why and alot of things have fell into place explaining why i am the way i am and why i act like i do and why im affected by social anxiety, i have sensory issues and much more, i struggle daily but still find a way to cope. Neurotypicals still accuse me of using my conditions as a “get out of jail free card” or “your using them as an excuse” but truthfully im not, they do not understand what is it like to be Neurodiverse and to live in a world not designed for us.

Thank you Lisa for sharing your story. I didn’t know what Neurodiversity was! Your story was so clear and relatable as many people struggle in silence, embarrassed and made to feel incompetence. You have given hope to many. Thank you.

Thank you so much for sharing your story, lovely to read. Neurodiverse employees are often working so hard to ‘mask’ at work and so to read your positive experience of being supported at work is really uplifting. I found it also very interesting to read the comments from other readers – there seems to be such a gap in access to assessment services, and little support (following diagnosis) to process emotionally what is, for many, a diagnosis later in life. Whilst it can be a relief to receive that diagnosis, it can also open up lots of questions and reflections around ‘what could have been’ and how life could have been different etc but there doesnt seem to be much out there to support employees with that element!

Thank you for sharing your story Lisa. Really helpful to read your experiences. I’m also neurodiverse & was diagnosed with Tourette Syndrome at age 57 by a GP. Still waiting to have the diagnosis confirmed by a neurologist nearly 2 years later! It’s sometimes a real struggle to manage at work despite reasonable adjustments. I try to spread awareness of what it’s like to be neurodiverse but I think it’s really hard for neurotypical people to understand.

my son has ASD and was diagnosed at 16 – had a terrible time through high school due to lack of understanding – “Stop trying to make me be less autistic. Just try and accept my autism. We’re still fully functioning members of society. If you can give us just a little bit, we will give you so much more.” – so true! – well done.

I have been trying to get my son an assessment for autism but the doctors are not interested. Shame

My daughter has Autism, BPD and depression. She has tried to lower her meds but suffers with side effects – akathesia and urges. She was diagnosed at 16 years old and is now 32 years old. Each day is different to the next for her, it’s a constant struggle for her in a world that she states is not suited to her way of thinking. She has tried many treatments but non of them worked. She would love to have a normal life, whatever normal is. Thank you for sharing your story. I have passed this onto her my daughter so that she is not alone in her struggle.

My experience with having Asperger’s in my work is completely opposite. My work colleagues were ok to begin, but I feel they don’t understand that neurodivergent people can look normal on the surface and don’t see the effort it takes to act in a way these people expect is massively tiring. I feel as if they don’t believe being neurodivergent is possible Like Lisa, I was diagnosed late in life. Some aspects are similar like being told I was depressed or had anxiety and prescribed anti depressants. What I’ve found is there is not much support for adults who get diagnosed later in life, which is such a shame.

It would be amazing if Unison could follow this up and help those who feel that they are neurodiverse get the help they need. It is so difficult to get diagnosed as an adult unless it happens alongside a child’s diagnosis. Please can there be some help for NHS staff to seek help in getting diagnosed?

I’ve been waiting over 2 years for an adult autism assessment. There’s too much to say, not enough time, space or energy in which to say it. Over constructed so many coping mechanisms, I no longer know what’s truly me anymore, so the assessment seems moot and I never belonged here anyway

Living in Northern Ireland I am currently on a 5 year waiting list through the NHS for my assessment. I work full-time & also on my second year of a part-time degree. It feels like there is zero support over here.

my life with severe irlens syndrome yet its always less spoken about and does not reach the hit list of neurodiversity. Many people are undiagnosed and like autism each person is affected individually… can come hand in hand with dyslexia although i don’t have this i have developed strong autistic traits over the years to help me manage. I find across the board people don’t understand invisible disability so we are given other lables such as weirdo, nuts, idiot etc… if you speak out for your own disability at least know the list is not complete under neurodiversity

Thank you Lisa for sharing your story of neurodiversity. I’m also Audhd with dyspraxia. It’s difficult to get through my day, I don’t feel that my employer is as supportive as they could be as they try to give me tasks that put me into overwhelm. If you drop the mask and they see your overwhelm you get sent for occupation health assessments for capability. I’m in constant limbo that I might loose my job even though i am capable I just need adjustments, but they get out of doing this by saying it doesn’t meet business needs. I’m glad that you have such a supportive employer as it makes a whole lot of difference.

Hi Lisa

Thank you for an amazing article. I am really proud for you that you are eventually getting the help you need.

I was diagnosed with Autism/Aspergers Syndrome 3 and a half years ago when I was 56. I’d known all my life that I was “different” to my peers, but school didn’t pick up on anything untoward. Looking back I can see that I must have masked this really well. Change was and still is a huge trigger for me. I struggled enormously with the transition from school to work, and was already depressed by this time. No one understood what I felt like or how I felt. The working environment is a minefield and hard enough to navigate at the best of times without having to educate your boss about your diagnosis. More recognition and help from employers would not go amiss.

I can highly recommend The Girl With The Curly Hair website. I attended a lot of their online webinars once I had been diagnosed and found them to be fantastically enlightening and empowering. I sat through the webinars and found myself going I can relate to that and that.

Thank you so much for sharing this article .

My twins who are 16 are both autistic.

I appreciate this read as there are similarities with both my twins. Poor social skills, anxiety, panic, poor maths abd concentration.

I worry about how my twins will adjust to a pathway of employment. Your story is so inspirational , I will share this with my twins, i now appreciate how those reasonable adjustments really impact . Lisa best wishes with your university studies , your daughter has a wonderful role model of a mother , she is destined to do well . Take care , Amena

I think I have picked this up late but should comment as I found it so encouraging. I was diagnosed with dyslexia in my early sixties while studying higher education for the first time with the OU. It is very comforting to find that others have neurodiversity diagnoses late in life too. Knowing why I struggle has helped me tremendously and I can empathise with all the “thoughts” expressed.

Thank you Unison for this article.